It is a bitter winter, and civil war is ravaging Kurald Galain. Urusander’s Legion prepares to march on the city of Kharkanas. The rebels’ only opposition lies scattered and weakened—bereft of a leader since Anomander’s departure in search of his estranged brother. The remaining brother, Silchas Ruin, rules in his stead. He seeks to gather the Houseblades of the highborn families to him and resurrect the Hust Legion in the southlands, but he is fast running out of time…

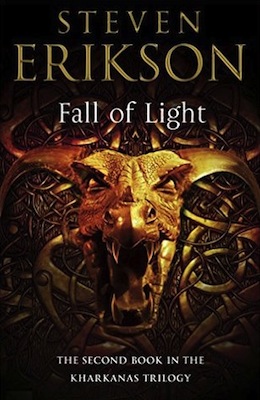

Steven Erikson returns to the Malazan world with Fall of Light, the second book in a dark and revelatory new epic fantasy trilogy, one that takes place a millennium before the events in the Malazan Book of the Fallen series. Available April 26th from Tor Books, Fall of Light continues to tell the tragic story of the downfall of an ancient realm, a story begun in the critically acclaimed Forge of Darkness. Read chapter four below, or head back to the beginning with chapter one!

FOUR

‘Lead unto me each and every child.’

A statement so benign, and yet in the mind of the Shake assassin Caplo Dreem it dripped still, steady as the blood from a small but deep wound, a heavy tap upon his thoughts, not quite rhythmic, like the leakage of unsavoury notions best left hidden, or denied outright. There were places into which an imagination could wander, and if he could but bar these places, and stand guard with weapons unsheathed, he would frighten off any who might venture near. And should one persist and draw still closer, he would kill without compunction.

But the old man’s thin lips, wetted by the words, haunted the lieutenant. He would as soon welcome a dying man’s kiss as see, once again, Higher Grace Skelenal grind out that invitation, in that wretched chamber of shadows, with winter creeping in under the doors and through the window joins, making dirty frost on floor and sill. Breath riding the chill air like smoke, the old man’s hands trembling where they feebly gripped the arms of the chair, and the avid thing in the deep pits of his eyes belonging in no temple, in no place proclaimed holy, in no realm of propriety or decency.

‘Lead unto me each and every child.’

He could remind himself that the old were useless in most ways. Their limbs were weak, their hearts frail, and their minds slipped and wallowed, or drifted along sordid streams few would call thought. Yet, for all of that, they could tend, severally, fecund gardens of desire.

Caplo would yield no pity in such places. He recoiled from plucking the luscious fruit, knowing well the poison juices each one harboured. Growth was no proof of health, and a garden made verdant with lust mocked every notion of virtue.

‘Your expression, friend,’ ventured Warlock Resh, ‘could turn a winter’s storm. I see a sky filling with fear as you bend your countenance upon the way before us, and that is not like you. Not like you at all.’

Caplo Dreem shook his head. They walked the rough, stony track side by side. The day was dull, the weather unobtrusive. The low hills to either side had lost all colour. ‘Winter,’ he said, ‘is the season that drains the life from the world, and the world from my eyes. There is something foul, Resh, in this denuded framework. I am not inclined to welcome the sight of shrivelled skin and raw bones.’

‘You shape only what you see, assassin, and see only what you would first shape. We cannot settle what it is that is inside with what it is that lies outside, and so toss them between our hands, as might a juggler with hot stones. Either way, our flesh burns.’

‘I would bless the blisters,’ said Caplo in a low growl, ‘and note the pain as real enough.’

‘What haunts you, my friend? Am I not the dour one between us? Tell me the source of your troubles.’

‘The hungers of old men,’ the assassin replied, shaking his head again.

‘We bend holy accord to profane need,’ Resh said. ‘Raw numbers. The Higher Grace spoke only what is written.’

‘And in so speaking, flayed the skin from pernicious appetites all his own. Is this the secret lure of holy words, warlock? Their precious pliability? I see them curl and twist like ropes. And all of this, no less, in the name of a god. Indeed, performed as ritual appeasement. How then to imagine that god’s regard as pleased, or approving? I confess to you on this road: my faith withers with the season.’

‘Faith I did not know you possessed.’ The warlock ran a hand through his heavy beard. ‘We are eager, it’s true, to confuse salvation with rebirth, and imagine a soul revived in its husk. But such ares are brief and easily ignored, Caplo. Skelenal and his appetites squirm in solitude—we have all made certain of that. Not a single child will come within his reach.’

Caplo shook his head. ‘Push on, then, through the centuries, and look once more upon our faith.’ He waved a hand, although the gesture faltered as his fingers made claws in the air. ‘Pliable words for the child’s pliable mind, which by prescription we knead and prod, and so make new shapes from old. And by this mishmash we cry out improvement!’ The breath gusted from him. ‘Nature yields its familiar patterns—those enfolding convolutions hiding under every skull, be it the cup of man, woman, child or beast. See our descendants, Resh, heavy in robes and brocaded wealth. See the solemn processions in flickering torchlight. I hear chants that have lost all meaning. I hear yearning in every inarticulate, guttural moan.

‘Heed me! I have found a truth. From the moment of revelation, of religion’s stunning birth, each generation to follow but moves farther away, step by passing step, and this journey down the centuries marks a pathetic transgression. From sacred to secular, from holy to profane, from glory to mummery. We end—our faith ends—in pastiche, the guffaw barely held in check, and among the parishioners a chorus of arrayed faces look on, helpless and bereft. While in the shadows behind the altar, foulfingered men grope children.’ He paused to spit on the ground. ‘Beneath the eyes of a god? Truly, who will forgive them? And truer still, my friend, how sweet is the nectar of their abasement! I suspect, indeed, that this thirst lies at the core of their weakness. To revel in unforgivable guilt is their soul’s own reward.’

Resh was silent for a long while after that. Ten strides, and then fifteen. Twenty. Finally, he nodded. ‘Sheccanto lies as one already dead. Skelenal shakes his palsied limbs loose in anticipation. And the assassin of the Shake contemplates patricide.’

‘I would cut the shrivelled cock at its root,’ Caplo said. ‘Blunt the precedent in a welling of blood.’

‘Your confession is not for my ears, friend.’

‘Then stop them with blessed ignorance.’

‘Too late. But many who mourn a graveside in silence will harbour condign thoughts of the departed, with none to know the difference.’

Caplo grunted. ‘We wear grief like a shroud, and pray the weave is close enough to hide our satisfied expressions.’

‘Just so, friend.’

‘Then you will not oppose me?’

‘Caplo Dreem, should such need arrive, I will guard your back on the night itself.’

‘In faith’s name?’

‘In faith’s name.’

The monastery and Skelenal were behind the two men now, shuttered away from the day’s steel light. Ahead, waiting on a low rise that seemed to bridge a pair of weathered hillocks, was Witch Ruvera. Ritually bound to Warlock Resh, assuming the role of wife to her husband, she wore a visage of cold stone, and its lines grew even more severe when she fixed her gaze on Caplo Dreem. As the two men drew nearer, she spoke. ‘Name me the company that welcomes an assassin.’

Sighing, Resh said, ‘Dear wife, Mother Sheccanto may be reduced to frail whispers, but we hear her desires nonetheless.’

‘Does the hag fear me now?’

The breath hissed from Caplo. ‘It seems you need no assassin to wield blades here, witch. Mother feared the risk you will take on this day, and charged me to protect you.’

Ruvera snorted. ‘She would know more of the power I have found. The company you will not name is one where trust lies strangled upon the threshold, and the gathering rustles like snakes in the straw.’

‘You invite unwelcome friends,’ said Caplo with a faint smile, ‘sleeping in barns. Rest your imagination, witch. I am but a guardian this day.’

‘With lies to protect,’ Ruvera said in a half-snarl, before turning away. ‘Follow, then. It is not far.’

Resh shrugged when Caplo cast him a bemused glance. ‘Some marriages aren’t worth consummating,’ the warlock said.

Ruvera barked a laugh at that, but did not look back at the two men.

‘By contemplation alone,’ said Caplo, ‘even I would flee into a man’s arms. I see at last the turn of your motivations, and indeed desires, friend Resh. Are we forever trapped in mockeries of family? Husband, wife, son, daughter—the titles assert, bold as spit in the face of the wind.’

‘I mistook them for tears,’ Resh said, grimacing. ‘Once upon a time.’

‘When you were no more than a child, yes?’

‘I will grant Ruvera this: she gave me confusion’s face, and every line made sharp its denial.’

The witch ahead of them laughed again. ‘A face, and a groping hand that awakened nothing. But that was my revelation, not his. Now,’ she added, drawing up on the edge of the rise, ‘observe this new consecrated ground.’

Resh and Caplo joined her and stood, silent, looking down.

The depression was oval-shaped, five paces across at its widest point, and eight in length. Its sides were undercut beneath the owing curl of long-bladed grasses, making the lone step down uncertain, but the basin itself was level and free of stones.

The strange feature was situated on a at stretch, part of which had been broken and planted by the nuns a few decades past—without much success—and beyond which rose low hummocks, many of which bore springs near the fissured rocks of their summits. The endless leak of water cut deep channels into the sides of those hills, converging into a single stream that only broke up again among the furrows of withered weeds. But the depression remained dry, and it was this peculiarity that made Caplo frown. ‘Consecrated? That blessing is not yours to make.’

Ruvera shrugged. ‘The river god is dead. Lost to the curse of Dark. Betrayed, in fact, but no matter. The woman on her throne in Kharkanas has no regard for us, and we would do well to shrink from her attention. Husband, seek out and tell me what answers you.’

‘Did you make this pit by your own hand?’ Resh asked.

‘Of course not.’

Caplo grunted and spoke before Resh could answer his wife. ‘Then let us ponder its creation, with cogent reason. See the drainage channels from the hills beyond. They reach a level to match the land around the basin, and if not for the irrigation scars would plunge into the ground and course onward, unseen. Yet here, below the crust of the surface, there was buried a lens of wind-blown sand and silts. So. The springs fed their water and the water found its hidden path, cutting through that lens, sweeping it away, thus yielding a depression of the crust.’ He turned to Ruvera. ‘Nothing sacred in its making. Nothing holy in its manifestation. It was the same hidden seepage that defeated the nuns who sought to grow crops here.’

‘I await you, husband,’ said the witch, her face set as if denying Caplo’s presence, and any words he might utter.

‘I am… uncertain,’ admitted Resh after a moment. ‘Caplo’s reason is sound, but it remains mundane, if not shallow. Something else thrives beneath the surface. No gift of the river god. Perhaps not holy at all.’

‘But powerful, husband! Tell me you can feel it!’

‘I wonder… is this Denul?’

‘If the sorcery here heals,’ Ruvera said in a low voice, ‘it is the cold kind. The hardening of scars, the marring of skin. It refutes sympathy.’

‘I sense nothing,’ said Caplo.

‘Husband?’

Resh shook his head. ‘Very well, Ruvera. Awaken it. Demonstrate.’

She drew a deep breath. ‘Let us take this expression of power, and make it into a god. We need only the will to do so, to choose to shape what waits in promise. We perch on a precipice here, but a ledge remains, enough to walk on, enough to stand upon. And from this narrow strand, we can reach out to both sides, both worlds.’

‘You invent from shadows,’ Caplo said. ‘I have never trusted imagination—or if I once did, no longer. Make your idol, then, witch, and show me it is worthy of a bow and scrape. Or palsied genuflection. Make me kneel abject and humbled. But if I see the impress of your palms and fingertips in the clay, woman, I will refuse worship and call you a charlatan.’

‘The hag you still call Mother shows her teeth at last.’

To that, Caplo simply shrugged.

‘Ruvera,’ said Resh, eyeing her, ‘I see you hesitate.’

‘I have reached down before,’ she replied, ‘and brushed… something. Enough to feel its strength. Enough to know its promise.’

‘Then why decry the assassin’s presence, wife?’

‘It may be,’ she said, eyes on the depression, ‘that the power requires a sacrifice. Blood. My blood.’ She swung to Caplo. ‘Do not defend my life. We have lost our god. We possess nothing, and yet our need is vast. I am willing.’

‘Kurald Galain’s squall descends to a secular war,’ Caplo said. ‘A civil war. We can stand outside it, now. No sacrifice is necessary, Ruvera. I may not like you, but I will not see you cast away your life.’

‘Even to stand apart, assassin, will need strength.’ She waved vaguely northward. ‘They will demand we choose sides, sooner or later. Captain Finarra Stone remains as guest to Father Skelenal, and asks that we commit ourselves in Mother Dark’s name. But our family remains unruly. Our patriarch dithers. He has no strength. Sheccanto fares even worse. We must choose another god. Another power.’

Resh clawed at his beard, and then nodded. ‘It falls to us, yes. Caplo—’

‘I will decide in the moment,’ the assassin said. ‘A knife commits but once.’

Ruvera hissed in frustration, and then dismissed him with a chopping hand. Facing the depression again, she closed her eyes.

Caplo stood waiting, unsure whether to fix his attention upon the witch, or the innocuous depression before them. Beneath his heavy woollen cloak he closed gloved hands around the grips of his knives.

Resh’s sharply drawn breath drew the assassin’s attention upon the shallow basin, where he saw the withered grasses lining it stir, then flatten away from the edge, as if they were the spiky petals of a vast flower. The cracked soil in the centre of the pit now blurred strangely, forcing Caplo to blink and struggle to focus—but his efforts failed, and the blurring deepened, the mottled colours melting, smearing. And now something was rising from below. A body of some sort, lying supine. In the instant of its rst appearance, it seemed but bones, peat-stained and burnished; in the next the skeleton vanished beneath the meat of muscles and the stretched strings of tendons and ligaments. Then skin slipped on to the form, rising from below like mud, and its hue was dark. Hair grew from that skin, covering the entire body, thickest beneath the arms and at the groin.

If standing, the creature would have been only slightly shorter than the average Tiste.

Caplo edged forward, tugged by curiosity. He studied the manifestation’s peculiar, bestial face—how the mouth and jaw projected, drawing out and flattening the broad nose. The closed eyes were nestled deep in their sockets, the brow half enclosing them thick and jutting. The forehead sloped back beneath the black, dense hair of the scalp. The creature’s ears were small and at against the sides of the head.

He noted the rise and fall of its narrow but powerful chest the moment before the creature opened its eyes.

Lips stretched back, revealing thick, stained teeth, and from its throat droned a dull, broken sound. The apparition then shivered, blurred and suddenly broke apart.

Ruvera cried out, and Caplo heard Resh’s curse. The assassin’s knives were out, but the weapons were no answer to his confusion, as in the place where a body had been lying moments before there now appeared a dozen creatures, sleek and black, weasel-like but larger, heavier. Fangs glistened and eyes ashed.

And then a full score of the beasts swarmed out from the pit.

Caplo heard the witch shriek, but he could do nothing for her as three of the creatures lunged towards him. He leapt back, slashing out with his knives. One edge sliced hide, but then the hilt snagged in fur and savage jaws closed around his hand. They crunched down through the bones, and heavy molars began grinding and tearing through. Screaming, Caplo tore his hand from the creature’s mouth.

Another beast hammered into his midriff, claws ripping to get through his clothing. He staggered back, disbelieving. The third apparition’s canines punched through flesh as its jaws closed on his left thigh. The weight pulled him down to the ground. He still held one knife, and twisting round, he drove the blade into the base of the beast’s skull, tore the weapon free and slammed it into the side of the animal clinging to his chest. The creature’s jaws, which had been striving to reach his throat, snapped shut, just missing the assassin’s neck. A wet cough sprayed blood out from its mouth. Rolling on to his side, Caplo stabbed again and felt death take his attacker.

The first apparition returned to bite into his upper arm, above the mangled hand. The pressure of those jaws crushed bones as if they were dry sticks. Caplo dragged it close with his arm and cut open its throat, down to the vertebrae.

He rolled again, pulling his arm loose from the now slack jaws. He staggered to his feet in a half-crouch, and, glaring, readied himself to meet the next assault. But the scene before him was motionless. He heard the barks of the creatures, but some distance away and fast dwindling. Warlock Resh knelt on the ground a few paces away, the carcasses of two beasts before him. His cloak had been shredded, revealing the heavy chain beneath it. Here and there, massive claws were snagged in the links, dangling like fetish charms.

Just beyond the warlock, Caplo saw a woman’s severed arm. The air reeked of shit, and, twisting slightly, he saw a long sprawl of lumpy intestines, stretching out as if they had been dragged. The nearest end plunged into a small huddled body, the legs of which had been chewed off at the knees.

‘Resh—’

The warlock reached out and tugged loose one of his short-handled axes from the nearest carcass.

‘Resh. Your wife—’

His friend shook his head, climbed drunkenly upright. ‘I will bury her here,’ he said. ‘Go back. Make your report.’

‘My report? Beloved friend—’

‘Leave us, Caplo. Just… leave us now, will you?’

The assassin straightened. He did not know if he would make it all the way back. His right arm streamed blood down through the torn flesh and shattered bones of his hand, making wavering strings between the ground and his fingertips. His left thigh felt swollen and hard, as if the muscle was turning to stone. Unlike Resh, he had not been wearing armour, and claws had torn across his ribs under his arms. Still, he turned away from his friend, raised his head, and slowly made for the trail.

My report. Blessed Mother and Father, Witch Ruvera is dead. A creature awakened, became many creatures. They were… they were uninterested in negotiation.

It seems, Mother and Father, that upon this land we would call our own, we are all but children. And this is the lesson here. The past waits, but does not invite. And to walk into its room yields only the death of innocence.

See me, Mother and Father. See your child, and heed the knowing in his eyes.

His blood was leaving him. He felt lightheaded, and the world around him was changing. The path vanished, the grasses growing higher—he fought them as he walked, struggling to pull his legs through the tangled blades. The winter had vanished and he could feel the weight of the sun’s heat upon his back. All around him, animals were walking the plain—animals such as he had never seen before. Tall, gracile, some banded, some striped or spotted in dun hues. He saw creatures little different from horses, while others bore impossibly long necks. He saw apes that looked like dogs, travelling on all fours, with thin tails standing high behind them. This was a dream world, an invented world that had never existed.

Imagination returns to haunt my soul. It arrives in a curse, ragged of edge and painfully sharp. Reason drip-drip-drips to spatter the grass. And what remains? Nothing but cruel, vicious imagination. A realm of delusion and fancy, a realm of deceit.

There is no paradise—do not mock me with this scene! The world is unchanging—admit to it, you fool! Raise up the hard truths of what truly surrounds you—the barren hills, the bitter cold, the undeniable heartlessness of it all! We know these truths, we know them: the viciousness, the cruelty, the indifference, the pointlessness. The stupid pathos of existence. For this, no reason to battle, to light on. Empty my soul of causes, and then—only then—shall I know peace.

Cursing, he fought against the mirage, but still the grasses pulled at him, and he heard their roots ripping free to the tug of his shins.

Now he was in shadows, entering a forest. Tangles of brush clogged the clearings at its edge, and then he was among straggly pines and spruce, the air cooler, and in the gloom beneath thick stands he saw bhederin, hulking and heavy, small ears flicking and red-rimmed eyes fixing on him, watching as he stumbled past.

Somewhere nearby a beast was ripping apart the bole of a fallen tree. He could hear the claws gouging and splintering the rotted wood.

A moment later he came upon the creature, and it was identical to those from the basin. It lifted its broad head, tilted a wood-flecked snout in his direction, and then bared its fangs in a snarl, before bounding away, running in the manner of an otter. Caplo stared after it, noted the blood on its hindquarters.

You show me this? I will remember you. I swear it. We are not finished, you and I.

The ground underfoot grew hard, and then he was crossing a at stretch of bedrock, its surface scraped and denuded. The blood draining from his hand made dull sounds as each drop struck the stone. Do I carry a brush? Does the paint drip? No. No brush—this flayed, heavy thing is what remains of my hand. No matter. The next rain will wash it all away.

It’s awake now. This thing of the past, this stranger who can become many. Pulled loose from the earth, reborn. And so very hungry.

Ruvera. You felt its slumbering power. You touched it with trembling hands, and thought to make it your own. But the past cannot be tamed, cannot be changed to your whim. The only slavery possible is found in the now, and its promise lurks among the ambitious—the fools so crowding the present and forever jostling, as if by will alone they could displace the undefended children, the children not yet born… They’ll put the rest of us in our place, to be sure, and if I am not among them, then I will stumble in shackles, just another slave. Another defenceless child.

Imagination was the enemy, but the bludgeon of will could defeat it, the stolid stupidity of every self-avowed realist incapable of dreaming could stifle it, like a pillow over a face. Chained to your desires, you would pull the world down to your pathetic level. Come then, make it barren and lifeless, colourless and unrelieved. I am with you. I see reason’s bloody underside. I see the value in this emasculation. The past is where imagination dwells—and we will have none of that. I surrender nothing, and by dispiriting the world, I become its master. I become the god—it is plain now, plain to me—the path awaiting us…

He shook his head, and the scene around him cavorted wildly. Stumbling, he fell to the hard ground, felt the brittle stubble of winter grasses stabbing the side of his face, the icy bite of frozen soil sinking into his cheek.

Reality’s kiss.

Someone was shouting. He heard the thump of footsteps fast approaching.

‘Revelation,’ Caplo whispered. ‘I hear the past calling. Calling.’

And it mutters, with a lick of withered lips, ‘Lead unto me each and every child.’

Revelation.

And then the women were all around him, and he felt soft hands. Smiling, he let himself drift away into darkness.

But not all the way.

* * *

Finarra Stone, captain in the Wardens, looked down upon the recumbent form of Caplo Dreem. The shutters, thrown back, offered up the uncertain light of the day’s dull overcast, filling the cell and settling a grey patina upon the man’s face. The sweat of fever gave that face the look of stained porcelain. After a long moment she turned away.

They had cut off the ruined right hand and forearm, sealing the stump with heat and some kind of pitch the colour of honey. The smell filling the room was that of burned hair and the suppurations of infection in the other wounds covering the assassin’s body.

She remembered her own battle against the same pernicious killer, not so long ago. But then Lord Ilgast Rend had been there, with the gift of Denul.

No one expected Caplo to live out the day.

She looked across to Warlock Resh, who sat red-eyed and haggard in a chair facing the cot. ‘I saw the bite marks,’ she said to him. ‘Similar to Jhelarkan, but smaller.’

He grunted. ‘Hardly. A wolf’s canines in the mouth of a weasel. Even a bear would run from such a beast.’

‘Yet they were the ones that fled, warlock.’

He licked chapped lips. ‘We’d killed five of them.’

She shrugged, glancing back to Caplo. ‘He would not have accounted for even one more. Leaving just you, surrounded, beleaguered on all sides. Armour or no, warlock, they would have taken you down.’

‘I know.’

When he said nothing more, she sighed. ‘Forgive me. I intrude upon your grief with my questions.’

‘You intrude with your presence, captain, but give no cause for the bitter taste in my mouth.’

‘It is said the Jheck of the south are a smaller breed.’

‘Not Jheck,’ Resh replied. ‘They were as I described them. Some animal long since vanished from the world.’

‘Why do you say that?’

He leaned forward and rubbed at his face, knuckling hard at his eyes. ‘Dispense with the scene itself, if you would understand its significance. Ruvera, my wife, discovered something ancient, buried. It slept in the manner of the dead. We believe that sleep to be eternal, do we not?’ And he looked up at the captain, his small eyes squinting.

‘Who can say?’ she replied. ‘Who can know? I have heard tales of ghosts, warlock, and spirits that once were flesh.’

‘This is a world of many veils,’ Resh said, ‘only one of which our eyes are meant to pierce. Our vision strikes through to what seems a sure place, solid and real and, above all, wholly predictable—once the mystery is expunged, and be sure: no mystery is beyond expunging.’

‘Those are not a warlock’s words,’ Finarra observed, studying him.

‘Aren’t they? By my arts do I not seek order, captain? The rules of what lies beyond the visible, the tactile? Find me answers to all things, and at last my mind will sit still.’

‘I would not think that journey outward,’ she said.

He shrugged. ‘Yes. There is symmetry. Outward, inward, the distances travelled matched and so doubled, yet, strangely, both seeking the same destination. It is a curious thing, is it not? This invitation to the impossible, and the faith that even the impossible has rules.’

She frowned.

Resh continued, ‘My wife spoke of the need for blood, for a price to be paid. I believe that she only half understood the meaning of that. To draw something back, from deep in death, into the living world, must—perhaps—demand the same among the living. If a warlock seeks to journey both outward and inward, in search of the one place where they meet, then the corollary is one of contraction, to collide in the same place, the same existence. For the dead to walk back into life, the living must walk into death.’

‘Then Ruvera’s life was the coin for this spirit’s resurrection?’

He sighed. ‘It is possible. Captain, the veils are… agitated.’ After a moment, he cocked his head, his gaze still fixed upon her. ‘Coin? I wonder. It may be… not coin, but food. Power, consumed, offering the strength to tear the veil between the living and the dead, and so defy the laws of time.’

‘Time, warlock? Not place?’

‘They may be one and the same. The dead dwell in the past. The living crowd the present. And the future waits for those yet to be born, yet in birth they are flung into the present, and so the future ever remains a promise. These too are veils. With our thoughts we seek to pry our way into the future, but those thoughts arrive as dead things—it is a matter of perspective, you see. To the future, both present and past are dead things. We push through, and would make the as yet unknown world a better version of our own. But with nothing but lifeless weapons to hand, we make lifeless victims of those yet to be born.’

She shook her head, feeling a strange, disquieting blend of denial and uncertainty. For all she could tell, Resh’s mind had broken, battered by shock and grief. She saw no clarity of purpose in his musings. ‘Return, if you will,’ she said, ‘to this notion of power.’

The man sighed, wearily. ‘Captain, there has been a flooding of potentialities. I know of no other way to describe sorcery—the magic now emerging. I spoke of three veils, the ones through time. And I spoke of the veil between life and death, which may indeed be but a variation, or a particularity, of the veils of time. But I now believe there are many, many veils, and the more we shred them, in our plucking of such powers, in our clumsy explorations, the less substantial they become, and the weaker the barriers between us and the unknown. And I fear what may come of it.’

Finarra looked away. ‘Forgive me, warlock. I am a Warden and nothing more—’

‘Yes, I see. You do not comprehend my warning here, captain. The newborn sorcery is all raw power, and no obvious rules.’

She thought of this man’s wife, Ruvera. It was said that the beasts had torn her limb from limb. There was shock in this, and for the Shake, terrible loss. ‘Have you spoken to the other warlocks and witches among your people?’

‘Now you begin to glean the crisis among us,’ Resh replied. He slowly lifted his hands and seemed to study them. ‘We dare not reach, now. No thoughts can truly pierce this new future.’

‘What of Mother Dark?’

He frowned, gaze still fixed on his hands—not an artist’s hands, but a soldier’s, scarred and blunt. ‘Darkness, light, nothing but veils? What manner the gifts given to her by Lord Draconus? What is the meaning of that etching upon the floor in the Citadel? This Terondai, that now so commands the Citadel?’

‘Perhaps,’ she ventured, ‘Lord Draconus seeks to impose rules.’

His frown deepened. ‘Darkness, devoid of light. Light, burned clean of darkness. Simple rules. Rules that distinguish and define. Yes, Warden, well done indeed.’ Resh pushed himself upright. He glanced at the unconscious form of his lifelong friend. ‘I must see this Terondai for myself. It holds a secret.’ Yet he did not move.

‘You have not long to wait,’ Finarra said quietly.

‘I have been contemplating,’ Resh said, ‘a journey of another sort. Into the ways of healing.’

She glanced at Caplo Dreem. ‘I imagine, warlock, the temptation is overwhelming, but did you not just speak of the dangers involved?’

‘I did.’

‘What will you do, then?’

‘I will do what a friend would do, captain.’

‘This is sanctioned?’

‘Nothing is sanctioned,’ he said in a growl.

Finarra studied the warlock, and then sighed. ‘I will assist in any way I can.’

Resh frowned at her. ‘The Shake refuse your petition. You are blocked again and again. You find us obdurate and evasive in turn, and yet here you remain. And now, captain, you offer to help me save the life of Caplo Dreem.’

She drew off her leather gloves. ‘Your walls are too high, warlock. The Shake understand little of what lies beyond.’

‘We see slaughter. We see bigotry and persecution. We see the birth of a pointless civil war. We see, as well, the slayers of our god.’

‘If these things are all that you see, warlock, then indeed you will never understand my offer.’

‘How can I trust it?’

She shrugged. ‘Consider my purpose as most crass, warlock. I seek your support. I seek to win your favour, that you might add your weight when I next speak to Higher Grace Skelenal.’

He slowly leaned back. ‘Of no value, that,’ he replied. ‘The matter is already decided. We will do nothing.’

‘Then I will leave as soon as I am able. But for now, tell me what I can do to help you heal your friend.’

‘No god looks down, captain, to add to your ledger of good deeds.’

‘I will measure my own deeds, warlock, good and bad.’

‘And how weighs the balance?’

‘I am a harsh judge of myself,’ she said. ‘Harsher than any god would dare match. I look to no priest to dissemble on my behalf.’

‘Is that a priest’s task?’

‘If not, then I would hear more.’

But he shook his head, rising with a soft groan. ‘My own dissemblers have grown quiet of late, captain. I look for no sanction now, in what I do. And for the Shake, no god observes, no god judges, and in that absence—forgive us all—we are relieved.’

She walked to the cell door and dropped the latch, and then faced the warlock. ‘And now?’

‘Draw your blade, captain.’

‘Against what?’

He managed a strained smile. ‘I have no idea.’

* * *

Caplo was being dragged across rough ground, a stony slope. Though his eyes were open, he could make out very little. A are of light blurred his vision, perhaps from a re, and the grimy hand gripping his ankle pulled him along as if he weighed nothing. He could see the strange splaying of his toes, and feel hairs being pulled by the stranger’s calloused hand, and the sharp stones gouged his bare back, tugging at still more hair.

Into a cave, then, rank with animal smells, rotting meat, and woodsmoke. The stone floor was greasy beneath him. There was no strength left in his body, and he felt his arms like thick, bristly ropes against the sides of his face as the limbs trailed up past his head. The cold, damp stone formed a crevasse into which his body slipped easily, as if it had gone this way a thousand times before. From somewhere deeper in the cave there was a dull, droning sound.

The passage narrowed, dipped and then climbed. His captor’s breath sounded harsh, whistling. The slap of its feet on the floor echoed ahead, like a drumbeat.

Everything drifted away, and when it returned the motion had ceased, and the space on all sides was filled with shifting bodies, barely seen in the light of embers filling skull-cups set on ledges on the walls. There was paint on those walls, he now saw. Beasts and hatchwork, handprints and upright stick figures, all rendered in red, yellow and black.

He tried sitting up, only to find that he was bound at the wrists and ankles. The thick ropes snapped taut then, raising him from the stone floor. He felt his head fall back, bouncing once, but then hands closed around the back of his skull, lifting until he could see down the length of his own body.

But the body was not his. Wiry hair covered it. His chest bulged like a bird’s. The strain on his joints burned, lancing pain down the length of his limbs to where the knotted ropes dug tight. He could not feel his hands and feet.

Dog-Runners hunting. I was asleep in a tree, my belly full. Above the scrubland, beyond the flats with their thin courses of trickling water slicking the clay. Animals licked the ground there with swollen tongues. They died in the heat, and there was food for all.

Dog-Runners hunting. No glory in driving a spear into a bloated carcass. They wanted a leopard, for its fur, its fangs and claws. Nothing to eat on a leopard. The liver kills. The heart is bitter. Leopards hate dying. They die in rage. They die filled with spite. Dog-Runners hunting leopard, eyes on the trees, shapes sprawled on thick branches. Blood-trails, streaks up the dusty boles, the prancing clashes of vultures and kites in a dance around the tree. The leopard looks down, interested but sleepy. Flies feed on its stained muzzle, tickling the whiskers.

All of this timeless, the ticking of the day’s heat, the night to come. No change comes to this scene. It could as easily be painted on a cave wall.

Dog-Runners hunting. I was asleep in a tree. One of me only. They saw me and thought, ah, the last of the Eresal in the hills, in the woodland, in the scrubland they now claimed. A young male, doomed to wander in search of a mate, a troop, but he was alone now. No other Eresal, not here, and how the others screamed when they died! They screamed, while the huge beasts they ran with ed the Dog-Runner spears, or died their own deaths in thrashing fury.

The very young had their skulls broken, their flesh cooked, their livers eaten raw.

Dog-Runners hunting.

Slingstones brought me down. Stunned by the fall. They rushed upon me, beat me senseless.

Leopard spirit. Claws marked the tree. They paid no heed.

We who lived fell away. We who lived returned to the tall grasses, the dark nights echoing with the yelps of hyena and the coughs of lion. We slunk back into the unseen rivers, when the world was timeless. We reached out to the spirits. We touched their hearts, and those hearts opened to us.

The ropes pulled with savage tugs, a panicky motion to mark sudden consternation. From the outer chambers of the cave there were screams now, echoing horribly closer and closer still.

Touch the leopard, run with the leopard, live the ways of the leopard.

They hunt alone.

Until the night the Eresal came to them. In the shifting grasses, the eye is easily deceived. But this is no aw of the beholder, no weakness of the witness. This is the blurring of magic. Who brought us this gift? This escape from extinction? There was talk of a mother who would rut everything in sight. A hoarder of seeds, a living vessel of hope.

A Mahybe.

In the cave, his kin were coming, committing terrible slaughter in the blood-splashed chambers.

He was one, bound here. He was many, and the many now came.

Hoarse cries rising around him, the ember light bursting as a skull was knocked to the floor. Rushing, jostling bodies, the clatter of weapons, and then his kin were among them.

The ropes fell slack, dropping him to the floor.

A body fell hard against him, one hand closing to make a fist in the hair of his head. In the crazed half-light, something gleamed. The Dog-Runner straddled him and he looked up into its face. The pale blue eyes were lit with terror. Then the hunter lifted into view a int knife and drove it into his chest.

In his dying breath, he laughed.

Because it was too late.

* * *

The cell had grown unnaturally hot. Finarra Stone sweated in her armour, her grip on the leather-bound handle of the sword slick and uncertain. Warlock Resh had knelt beside Caplo Dreem’s cot, head bowed, his hands resting palm-up on his thighs. She had not seen him move in some time.

Her stay in this monastery had gone from days to weeks. News from beyond the walls was virtually non-existent. And yet she found something almost comforting in this imposed ignorance, as if by remaining here, witness to the small lives bound up in all their small gestures of priestly custom, she could hold back the world beyond—as if, indeed, she could halt history in its tracks. She now believed she understood something of what drew men and women to places such as this one. A deliberate blindness to invoke the lure of simplicity seemed the gentlest of rituals, with only a drop or two of blood spilled.

If gods could truly offer up a simple world, would not every mortal soul fall to its knees? As buildings crumbled, as fields fell fallow, as injustices thrived in blessed indifference. She had seen temples and sacred monuments as gestures of diffidence, stone promises to permanence, but even stone cracked. There was nothing simple in the passing of lives, in the passing of entire ages. And yet, for all her convictions—that verged on the worship of complexity—something deep in her heart still cried for a child’s equanimity.

But the Shake places of worship were now lifeless. They had become tombs to their slain god. The faith of these people here was blunted, like fists pounding a sealed door. The simplicity they had found, she realized, was no virtue, and if a child’s face could be conjured from this, it was dark and obstinate.

They would stand to one side, Resh said. But she believed that position was suspect. They would find themselves not to one side at all, but in the middle.

This warlock here, risking his life for his friend, was the last soldier available to Skelenal and Sheccanto, although ‘soldier’ was perhaps the wrong word. These men and women were trained in the ways of battle. But of leaders they had but one, now. A grieving man, a man consumed with doubts.

It was difficult to gauge the passage of time, but she was growing weary of standing, and the strain of staying alert clawed down the length of her nerves. She let the tip of her sword rest against the wooden boards of the floor.

‘Abyss below!’

Resh’s bellow startled her and she staggered back a step. Before her, the warlock had lurched upright, flinging himself on to the body of Caplo Dreem, as if seeking to hold the unconscious man down.

Wondering, frightened, she dropped her sword and lunged forward.

Caplo Dreem was not resisting Resh—he was not struggling at all—and yet she saw his form blur, as if it was moments from vanishing. The warlock grasped the assassin’s right arm and leaned down on Caplo’s chest. ‘Take the other arm!’ he shouted. ‘Do not let him leave!’

Leave? Bafled, she moved round to the left side of the cot and grasped Caplo’s left arm with both hands. The stump, she saw, had bled through the heavy knot of bandages. Horrified, she saw the talons pierce the gauze. ‘Warlock! What is happening?’

‘Admixture of blood,’ Resh said in a rough hiss. ‘The old one within him mocks the child still—he drags it along. No abandonment. No murder. They will dwell together—I hear it laughing.’

‘Warlock, what has your magic unleashed here?’

The talons had sliced through the bandages, fingers splaying as they grew. On Caplo’s sweat-lathered arm, Finarra saw a mottled pattern forming on the skin, darkening to form a map of dun spots that seemed to oat on a shimmering surface of gold and yellow. The flesh under her grip felt as if it was melting away.

‘Not my doing,’ Resh said in something like a snarl. ‘I couldn’t get in. Even with the sorcery I awakened, I couldn’t get in!’

A guttural growl emerged from Caplo, and she saw that he had bared his teeth, although his eyes remained shut.

‘He must not veer,’ said Resh.

‘Veer? Then indeed they were Jheck—’

‘No! Jheck are as children in the face of this—this thing. It is old, captain—gods, it is old! Ah, Ruvera…’

The spots were fading. She saw the talons retracting into fingers. His forearm and hand had grown back, slick with blood and the torn fragments of scorched flesh. The wounds of the thigh were but faint scars now, all signs of infection gone.

‘He retreats,’ Resh said in a frail gasp. He looked across at her, his eyes wide and frightened. ‘Understand me, captain, none of this was my doing. They but wait, now.’

‘They?’

‘I spoke of the revenant awakened by my wife—how one became many.’

‘And this now afflicts Caplo Dreem?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is it an illness? A fever?’

‘I think… no. It is—’ He shook his head. ‘I cannot be certain. It is… an escape.’

‘From what?’ She leaned back, released Caplo’s arm, and studied the warlock. ‘From death itself? He was going to die—’

‘No longer. But I can say nothing more, captain.’

‘And when he awakens? Your friend—will he be as he once was?’

‘No.’

The fear in his eyes would not fade. Looking into them, she thought of caged beasts.

‘Remain with me,’ he then said. ‘Until he awakens.’

Straightening, she searched the floor until she spied her abandoned sword. She strode over, crouched and closed her hand about the damp, cold grip.

Someone pounded on the door, startling them both.

‘Go away!’ Resh roared.

* * *

The line of hills ended in a series of ridgebacks, steep-sided and bare of all growth. The soil was stony, the hue of rust, forming fans at the base that spread out over the edge of the plain. Sharp-edged rocks studded these fans, glinting like gems in the pale, wintry light.

Kagamandra Tulas stood facing east, looking out over the flats to the distant line of black grasses. Below him the red fans of silt had the look of draining wounds, bleeding out across the dull grey clays of the plain. He had made his camp just behind this last serrated line of the hills, sheltered against the bitter winds that swept down from the northeast. In the midst of tumbled, fractured boulders, near a massive nest of withered branches and trunks from some seasonal flood, he had built a small wooden shelter, tucked against an overhang. The opening faced on to a small firepit, where he cooked his meals, slowly working through the serendipitous cache of fuel. A dozen paces along the crevasse was a cut to one side that led to a cul-de-sac where he had hobbled his horse.

Somewhere between his departure from Neret Sorr and here, the tide of determination and will had died away. A better man would have pushed on in defiance of his own sordid failings. At the very least, he would have completed his journey to the winter fort of the Wardens, or perhaps onward from there, to the Shake denizens of Yannis Monastery or Yedan. And from such places Kharkanas was not far, not far at all. Each step offered its own momentum, something even a mule understood.

Heroic journeys, as sung by poets, never stumbled against a lack of fortitude in the hero. The inner landscape of such men and women was something strange and foreign to the audience, and so it was ever intended, as a poet’s purpose was neither simple nor innocent.

No mortal could set himself against such a hero. Perhaps that was the secret lesson in such tales. But Kagamandra had long since abandoned the romance of heroism, as if life could be lived only from a distance, with oneself that figure, forever remote on the horizon, crossing an arid landscape with every step a battle won, where every war was a war worth fighting. In this scene, there was no promise to draw closer. Details surrendered to the necessity of purpose.

He had once believed that such tales would be spun of his own life, of his exploits on the eld of battle. He had once yearned for the attention of poets—in the days when songs showed no bitter underside, before the world grew jaded with itself.

Sharenas—cousin to Hunn Raal and the woman who had quite possibly stolen his heart—had urged him to ride to his betrothed. Was that not a heroic quest? Did that not invite a song or a poem? Would not such a journey win for him Faror Hend’s undying love? But as he rode out from Neret Sorr, leaving behind that wretched, reborn army, did he truly believe any of that? Should he find her, should he come at last face to face with Faror Hend, what would she see? A desperate, pathetic old man, who would grasp hold of her in the way of all old men: as if she embodied his long-lost youth. How could she not inch from his approach? How could she not distrust anything he had to say?

Vows of freedom were like a dog clamping jaws on its own tail. With the promise between its teeth, it could run for ever.

The sky to the east was heavy with clouds, polished iron and promising snow. He was running low on food and these hills were mostly barren, barring a few rabbits that still eluded the snares he’d set. The forage he’d brought with him for his horse was almost all gone and the animal was weakening by the day. The exigencies of survival should have already forced him to resume his journey, but even this impetus had yet to drive him from his lair.

His father had known him for a self-indulgent child, and, should the man’s spirit still linger, it would yield no surprise when looking now upon its only surviving son. The privilege of dying while still filled with promise had belonged to Kagamandra’s brothers. Somewhere leagues to the south, three cairns made islands on the plain, and around each of them the grasses grew verdant, and come the spring flowers would blossom in colourful profusion about the stones.

He had spent years telling himself to not begrudge the liberation his brothers had found: that blessed release from expectation and the sordid disappointments that followed.

I do not love her. That much is clear. Nor do I wish her love. I am a ghost. I linger on through lack of will.

In the distance, riders had emerged from the wall of black grasses. Some led horses bearing what looked like bodies. He had been watching the troop for some time as they walked their mounts alongside the sharp edge of Glimmer Fate. They were now directly opposite him and would soon pass as they continued south.

There was an ancient saying his father had been wont to use, wielding the words like weapons to batter down his children. A hero’s name will live for ever. Die forgotten, and you have not lived at all. When Kagamandra had returned home from the wars, the lone survivor among his father’s children, he had been a hero of renown, a warrior raised high on the shield of nobility—gifted with title and honour. His father had stared at him with lifeless eyes and said nothing.

In the following year, the old man elected to waste away to nothing, behaving as if all his sons had died. He never again spoke Kagamandra’s name. You’d forgotten it, perhaps. And so I, who lived, never lived at all. Your favourite saying, Father, proved a lie, when at last it settled at your feet. Or was it you who failed it?

No matter. Not a single reward did not taste bitter once I returned home. I did not return to find my bride awaiting me. I did not return to my father, for the news had preceded my arrival, and when at last I came, he was already standing in the shadow of death.

He did not love Faror Hend. He’d not even wanted her. When he huddled under the furs at night, hearing the distant cries of the lizard wolves of Glimmer Fate, he thought not of that young woman. He thought, instead, of Sharenas.

How many fatal choices could a man make? Many, because even death need not be sudden. It can be measured out like sips of poison. Each day can be greeted as if it too had died, and but awaited your arrival. How many deaths could a man endure? I still walk a field of corpses, and not one of them has anything good to say, but I have learned to look them in the eye and not inch. I thank my father for that.

He stepped away from the ledge, worked his way down the narrow, crooked path to his camp.

He fed the last of the forage to his horse and then gathered and bound his bed furs, strapped on his sword and checked over the rest of his gear before saddling his scrawny mount.

A short time later, astride his horse, he emerged from the defile, swung the animal over the crest and rode down a red slope of silts to the hard, frozen plain. Snowflakes spun down from the sky. He set out at a slow canter, to work some heat into the beast’s legs.

* * *

Bursa re-joined them. ‘It is Kagamandra Tulas, commander.’

Calat Hustain rode on for a moment longer, and then reined in. The rest of the troop drew up around their leader.

The veteran sergeant settled in the saddle, gloved hands resting on the horn. Since the day on the Vitr shore, Bursa had not slept well. Each night pulled him into a fevered world where dragons wheeled overhead whilst he ran across a vast, featureless plain. His arms were burdened with strange objects: a silver chalice, a crown, a sceptre, a small chest from which gold coins spilled.

In this nightmare, he was the lone protector of these treasures, but the dragons were not hunting him. They but circled overhead like carrion birds. They waited for him to fall, and onward he ran, inching from their vast shadows that played over the ground ahead. The coins kept falling, bouncing and scattering in his wake—there seemed to be no end to them. And when the sceptre slipped through his grasp and fell, he found another one, identical to the last, still in his arms.

The crown, he saw, was broken. Mangled. The chalice was dented.

The Eleint were patient overhead. He could not run for ever, and there was no place in which to hide. Even the ground under his feet was too hard for him to make a hole, to bury his precious hoard.

Awakening in the dawn, he was red-eyed with exhaustion, and he found himself repeatedly searching the sky during the course of each day’s travel.

They had seen no further sign of the terrible creatures. The Eleint had plunged into this world through a gaping rent in the air above the Vitr, only to then vanish. Somehow, this was worse—and during the day Bursa almost longed to see one, a minute talon-slash of black off in the distance. But this desire never lasted the journey into sleep.

At Calat Hustain’s command he had ridden back to discern the identity of the lone rider following them. It seemed now that they would await the man. Bursa glanced across at Spinnock Durav, and felt a stab of something close to resentment. The young could weather anything, and among them there were those who stood out even among their peers, and Spinnock Durav was such a man. Was it his perfect features that made certain the founding stones of his confidence, or did some residue of untrammelled self-worth seep out to settle into his face, creating the illusion of balance and open equanimity?

Bursa was tasked with protecting the young Warden by none other than Captain Finarra Stone. But it had been Spinnock’s warning cry that had saved everyone, down at the shoreline. Or perhaps Bursa misremembered—it had been a fraught time. But when he revisited that shout in his memory, it came in Spinnock’s voice.

I begin to obsess. Again. All my life, this same game. I but move from one to another. No peace, no hope of rest. I run like the fool of my dreams, carrying the last treasures of Wise Kharkanas.

Eleint.

Spinnock Durav. She should never have charged me with this task. Should never have invited me to fix my attention upon him. Did she guess nothing of the envy hiding within me, and how it would find Durav? Obsession runs down the same path, again and again. Each time, the same stony trail. Envy is a sharp emotion. It has purpose and it has power. It needs someone to hate, and it seems I have found him.

Spinnock Durav caught his eye and smiled. ‘Another two days of this, sergeant, and then we’re home.’

Bursa nodded, tugging at the strap on his helm, where it had begun rubbing his throat raw. The air was cold and it was dry, and his skin never did well in this miserable season. He leaned back and scanned the dull sky. The snow spinning in the air seemed to fail in reaching the ground.

‘Cold up there, I’d think,’ said Spinnock, edging his mount up alongside Bursa. ‘Even for a dragon.’

Bursa scowled. Of course the man had noted his habit, and now teased him for it. ‘My bones ache,’ he said to Durav. ‘Tells me a storm is coming. I but seek its measure.’

Spinnock offered another quick smile and nodded. ‘I thought we might outrun it, sergeant.’ He twisted to watch the approach of Kagamandra Tulas. ‘But it seems not.’

Only then, in following the young man’s gaze, did Bursa see the swollen bank of the storm front, spread across the north horizon. Grunting, he shook his head. His thoughts stumbled with weariness, building reckless bridges in his mind.

Calat Hustain tapped heels against his horse’s flanks and worked his way free of his troop, reining in just beyond the last horses with their bound corpses as Kagamandra Tulas finally arrived.

‘Captain,’ said Calat in greeting. ‘You are far from the track between Neret Sorr and our winter camp—have you been looking for me? What dire Legion pronouncement must I face now?’

The grey-bearded warrior was unkempt, his heavy cloak filthy. The horse he rode was gaunt. He held up a gauntleted hand as if to forestall Calat’s questions. ‘No word from Urusander accompanies me, commander. I travel upon my own purpose, not that of the Legion.’

‘Then you have no news?’

Bursa saw Kagamandra hesitate, and then shrug. ‘Winter is a yoke upon all ambitions. But I would say beware the spring, Calat Hustain.’

‘Must every soldier of the Legion threaten me?’

‘I am a captain no longer, sir. My old allegiances are done.’

Calat Hustain was silent for a moment, and then he said, ‘Cut off the limb. Still it bleeds.’

Kagamandra squinted across at Calat, and then growled something under his breath. He shook his head, and his anger was evident. ‘If my warning of a coming war stings you like a thorn, then, commander, I wonder what wilderness grows riot in your skull. For the sake of your Wardens, I advise you hack your way free. The threat of war greets all of us, or would you claim special privilege in the face of its tragic promise?’

‘Yet you would seek the Wardens,’ said Calat. ‘Kagamandra, Faror Hend will not be found at our winter camp.’

‘Then tell me where I will find her.’

‘I cannot, beyond what I have already said. She does not await you at this trail’s end.’

Bursa knew that his commander could have been more forthcoming. He could not decide if Calat’s pettiness shamed him or left him satisfied. There had been nothing inviting in Calat’s initial greeting, and now it seemed as if, in understanding the reason for Kagamandra’s journey, Bursa’s commander stood before a caged dog, jabbing between the bars with a sharp stick.

We are all tired. Battered by circumstance. Pity grows sparse in this season.

With a nod, Kagamandra collected his reins. He set out towards the hills to the west.

‘Wise enough to find shelter,’ Spinnock murmured. ‘I wonder if we should do the same.’

‘And follow Tulas?’ Bursa asked in a hoarse whisper. ‘I invite you to offer our commander that suggestion.’

Although Spinnock answered that with a smile, at last Bursa saw a hint of frailty in it, and as the young Warden remained silent when Calat gestured and the troop resumed its southward trek, skirting the edge of Glimmer Fate, the sergeant found himself chewing a certain pleasure in this modest victory.

That was worthy guarding, was it not? Do not make a fool of yourself to your commander, Spinnock Durav. Best speak to me first, believing as you do an ease between us, and in me a secure home for your foolish words. And if I should hoard them, well, that is my business.

He was thinking, again, of the vast empty plain, on which shadows raced as dragons sailed the sky overhead, his arms burdened, and the breath ragged in his throat, when the winter storm reached them in a gust of bitter cold wind, and a flurry of icy sleet.

* * *

Narad crouched close to the fire, watching the others who had come in answer to Glyph’s summons, though he knew not the nature of that invitation. It seemed as if there were voices in this ruined forest that he could not hear. Blunted and dulled by his sordid self, all sensitivity was lost to him. With his eyes, he was reduced to indifferent observation; the few sounds he heard were nothing more than mundane camp sounds of hunters gathering; the taste in his mouth was bitter with stale scraps of food and brackish water. With this prison that was his body, he could feel frozen ground underfoot, and the brittle fragility of the twigs and branches that he fed into the flames. This, then, was all that he was. No different from the half-dozen scrawny dogs that had joined their makeshift tribe.

The Deniers surrounding him were strangers, in ways Narad could barely fathom. They moved in near silence, spoke rarely, and seemed obsessed with their weapons—the hunting bows, and the bewildering array of arrows, each one somehow distinct in its purpose, each made unique in the twist of the etching, or the barb, the length of shaft or the wood used, or the material from which the point was fashioned. With matching meticulousness, these men and women, and even the youths among them, worked also on their long-bladed knives, with oil, with spit, with various sands and gritty clay. They unwrapped and wrapped again the antler or bone handles, using leather, or stringy grasses, or gut. A number carried throwing spears, and made use of weighted atlatls made of soapstone, or greenstone—these artfully carved in sinewy, serpentine patterns that made Narad think of water in streams, or rivers.

The obsessions invoked patterns, ways of moving that were repeated without variation. The rote dispensed with the need for words, and no paths were crossed, no task interrupted, nothing to change one day from the next. From this, Narad had begun sensing the way of living among these people of the forest. Circular in its seeming mindlessness, no different from the seasons, no different from life’s own cycle.

And yet, in purpose, Glyph’s tribe was bending itself to the task of murder. All this was preparation, offering up a deceiving rhythm that could lull a man unaccustomed to patience.

A man such as me. Too clumsy to dance. He had looked over the Legion sword he now carried. It seemed serviceable. Someone had taken care of the honed edge, smoothing out burrs and softening nicks. The scabbard required no repairs. The belt’s leather was burnished and worn, but nowhere overstretched. The rivets were firmly in place, the buckle and rings sound. His examination had taken but a score of breaths.

And now he waited, watchful but emptied of feeling, and found for his self a greater affinity with the wandering dogs than with these hunters, these avowed killers.

Patterns were something he understood. All that he was, and had been, or would be, ever circled around some thing, some force—he imagined it as an iron stake driven deep into the ground, and affixed to it was a solid, thick ring. Whatever he did, whatever he planned to do, was bound to that ring, in knots no mortal could break. Sometimes the rope felt long, looping, eager to unfurl and let him run and run far, but never as far as he had imagined, or dreamed that he could. And so he would be pulled round, to the right or the left, and though he kept running, he but tracked a circle. The stake stood in a glade, with all the earth around it beaten down, the grasses worn away, the trails circling and circling.

He had killed and would kill again. He had found himself plucked loose from the company of others, singled out, scorned and belittled and mocked. Every promise of brotherhood proved an illusion. There had been no women strong enough to cut the rope, or work loose the stake itself. Instead, he but dragged them into his coils, pinned them down, took what he needed but never found—never, never that way. Our bodies close in seeming intimacy, but the truth is a savage thing. What I long for… what I longed for, was something tender.

But that language was never given me. Give shape to my frustration, then, in brutal rape, in the empty triumph of power. I could take a thousand women this way, into my embrace, where the grasses are worn down and dust stings the eye, and never find what I seek.

Patterns. Round and round I go, nailed in place, trapped, doing again what I did before, and again, and again.

He but waited for the falling out, the first cruel comment, the birth of barbed words flung his way. Wasn’t it enough that he was not of this forest? That the hunters only tolerated him because Glyph had told them to? How soon would the resentment of that eat through this thin civility?

Better had Glyph sent an arrow into his chest, with point of int, iron, bone or antler, in spinning flight, the length of shaft perfectly suited, the wood elegant in its supple answer to the bow’s string.

There were thirty or so Deniers in this camp now. If they each had a tale to tell, it was whispered in that voice Narad could not hear, the mouths moving behind masks, and all the while the quiet, maddening preparations continued. Round and round and—

Glyph moved to settle into a crouch beside him. ‘I name you the Watch. In our old language: Yedan.’

Narad grunted. ‘I do little else.’

‘No. For the time of night, when you wake. When you rise and walk the camp. The time of night when your haunts return to you. Your nerves tremble. A restless thing takes you, a thing you cannot name, unless you clothe it in your deepest fears. You wake and stand, when others would fight back into sleep, into losing themselves again. This is a terrible vigil, a solitary vigil. It is the vigil of one who stands alone.’

With the toe of one boot, Narad pushed the end of a branch deeper into the re. He could think of nothing to say. The other names he had earned had stung. But not this one. He wondered why.

‘My hunters honour you,’ said Glyph.

‘What? No, they ignore me.’

‘Yes, just so.’

‘You call that honouring? You Deniers—I don’t understand you.’

‘The Watch is always alone. Their story makes them so. We see in your eyes, friend, that you have never known love. Perhaps this is necessary, for the task awaiting you.’

Narad thought about Glyph’s words. He had set for himself a task. That much was true. But he had doubt as to the purity of his purpose: after all, that Legion troop was witness to his shame, and the faces he saw, at night—the ones that started him awake with the sky black overhead—were ones he wanted to cut away, cut down, crush under his heel. My shame. Each of them. All of them. He could raise high his vow, voice her name like a prayer, and announce himself the weapon of her vengeance. And even then, he would hear his own whispered hunger, heart-wounded and pathetic, for something like redemption.

There were mines where worked the fallen and the failed, the unforgivable fools who carried with them their unforgivable deeds. They crawled into the earth, burrowed under heavy stone and layers of rock. They dug their way through their unforgiving world, and deemed that a kind of penance. He should have gone to such a place. If only to shatter the bedrock holding that iron stake, shatter it, see me burst free, to run a straight path—straight as an arrow, straight over the nearest cliff.

To Glyph he now said, ‘My task is vengeance. Against my own shame. Others took… bits of it. I need to hunt them down and take it back. If I can do that… if I can reach that, that place…’

‘You will then be redeemed,’ said Glyph, nodding.

‘Which must not be, Glyph. Must never be allowed to happen. For what I did… no redemption is possible. Do you understand?’

‘The Watch, then, must guard a bridge destined to fall. The Watch who stands, and stands fast, is our harbinger of failure.’

‘No. What are you saying? This—this crime of mine—it has nothing to do with you Deniers. Your cause is just. Mine isn’t.’

‘The two must recognize each other, friend, and then together look upon the deed between them. See how it is, in the end, one and the same.’

Narad studied the warrior. ‘It seems you have already invented me, Glyph. Found a way to, well, hammer me into your way of seeing the world. I am an awkward fit, don’t you think? Best find another, someone else, someone with less… less history.’

But Glyph shook his head. ‘We do not fear this… your awkward t. Why fear such a thing? A world made smooth allows no purchase. Neither a way into it nor a way out from it. It is closed on itself. It makes its own answer, and so lies undisturbed by doubt.’

Narad scowled at the re. ‘What are we waiting for, Glyph? There are soldiers I need to find and kill.’

Glyph waved a hand, and then straightened. ‘Visitors are coming. They will soon be here.’

‘All right. Coming from where?’

‘From a holy shrine. From an altar black with old blood.’

‘Priests? What need have we for priests?’

‘They walk the forest. For days now. We have been following their progress, and it seems that it will bring them here, to this camp. So we wait, to see what comes of it.’

Narad rubbed at his face. The ways of the Deniers remained a mystery. ‘When do they arrive, then?’

Glyph set a hand on Narad’s shoulder. ‘Tonight, I think. In your time of waking.’

* * *

In his dream Narad walked a shoreline of fire. He held a sword in his hand, but trailed its tip through the sand, and the sand was spitting sparks and aring as embers were pushed to the sides of the wavering furrow left by the weapon’s point. The blood on the blade had burned, curled black. He was exhausted, and he knew that somewhere behind him he had left behind a much larger wake, one made up of corpses piled to either side.

Flames surrounded him, rising high as burning trees. Ash rained down.

There was a woman beside him. Perhaps she had always been there, but he had no sense of time. He felt as if he had been walking this shoreline for ever.

‘You’ll find no love here,’ the woman said.

He did not turn to her. It was not yet time to see her, to meet her eyes. She walked like a sister, not a lover, or perhaps just a companion, but not a friend. When he answered, a tremble of shock followed his own words. ‘Yet here I will stand, my queen.’

‘Why? This is not your war.’

‘I have been thinking on that, highness. On war. I have been thinking that it does not matter where the war is, or who fights it. Or whether we hold blood ties to the slayers, or not. It could well be on the other side of the world, fought by strangers, for reasons we cannot even understand. None of that matters, highness. It is our war nonetheless.’

‘How so, Yedan Narad?’

‘Because, in the end, nothing divides us. Nothing distinguishes us. We commit the same crimes, taking lives, holding ground, yielding ground, crossing blood-drenched borders—lines in the sand no different from this one here. With fires at our backs, and fires ahead—I thought I understood this sea, highness, but now I see that I did not understand it at all.’ He raised his sword and pointed its tip at the shimmering, flame-wrought surface beyond the shore. The weapon bucked and trembled in his hand, as if bound to its very own will. ‘That, my queen, is the realm of peace. We dream of swimming it, but when at last we do, we but drown.’

‘Then, O brother, you give us no hope, if war defines our existence, and peace our death.’

‘We all commit violence on ourselves, highness. It is more than just brother against brother, sister against sister, or any other combination you care to imagine. Our thoughts wage savage mayhem in our skulls, with no respite. We fight desires, wave banners of hope, tear down the standards of every promise we have dared utter. In our heads, my queen, is a world that is without peace, and by that description we define life itself.’

‘You question your purpose, brother,’ she said. ‘After all this. It is no surprise.’

‘I was a lover of men, Twilight—’

‘No. That is not you.’

Confusion took him and he almost stumbled. Drunkenly righting himself, he let the sword drop again, the point sending up a burst of sparks as it struck the sands. They walked on. He shook his head. ‘Forgive me, it nears the time.’

‘Yes. I understand, brother. The night crawls; even should we lie in sleep and so see nothing of it, still, it crawls.’

‘I would have you, my queen, uproot the spike.’

‘I know,’ she replied in a soft voice.

‘Their faces were my shame.’

‘Yes.’

‘So I cut them all down.’

‘White faces,’ she murmured. ‘Not sharing our… indecision. We are their only shadow, brother, and in that, we can never lie to them. You did what you had to do. You did what they demanded of you.’

‘I died in my sister’s arms.’

‘Not you.’

‘Are you sure, my queen?’

‘Yes.’

He halted, shoulders hunching, head bowing. ‘Highness, I must ask you—who set this world afire?’

She reached out to him, one soft gore-smeared hand touching the line of his jaw, lifting his gaze to her own. The rapists had done their work. There was no forgetting that. He remembered the feel of her broken body beneath him, and the ragged mess that had been her wedding dress. With dead eyes, she looked upon him, and her dead lips parted, to utter the dead words, ‘You did.’

* * *

Narad’s eyes blinked open. It was night. The few fires had burned down, and the scorched stumps of trees stood thin and black on all sides of the camp. The others were asleep. He sat up, tugged aside the ratty furs of his bedding.

He welcomed her haunting, but not the illusions it delivered. He was not her brother. She was not his queen—although perhaps, in some ways, he had made her so—but that honour, as he felt it in that place, on that fiery shoreline, was not his alone. It was an earned thing. She led her people, and her people were an army.

Wars inside make wars outside. It has always been this way. There is nothing left, but everything to fight for. Still, who dares imagine this a virtue?

He lifted hands to his scarred, mangled face. The aches never quite faded away. He could still feel her grimed fingers along the line of his jaw.

Motion caught his eye. He quickly stood and faced it. Two figures were walking into the camp.

The heavier of the two reached out to stay his companion, and then strode towards Narad.

He is not Tiste. He wears the guise of a savage.

But the one who waits behind him, he is Tiste. Andii.

The huge stranger halted before Narad. ‘Forgive me this,’ he said in a low, rumbling voice. ‘There is heat in the earth beneath us. It burns fiercest beneath your feet.’ He paused and tilted his head. ‘If it eases you, consider my friend and me as… moths.’

The others in the camp had awakened, were sitting up, but otherwise not moving. All eyes were fixed upon Glyph, who had risen and was joining Narad.

The stranger bowed to Glyph. ‘Denier, will you welcome us to your camp?’

‘It is not for me,’ Glyph replied. ‘I am the bow bent to the arrow. In this matter, Azathanai, Yedan Narad speaks for us.’

Narad started. ‘I’ve not earned any such privilege, Glyph!’

‘This time of night belongs to you,’ Glyph replied. ‘This is not where you stand, but when.’

Narad returned his attention to the stranger. Azathanai! ‘You are not our enemy,’ he said slowly, inching at the faint question in his tone. ‘But the one behind you—is he a Legion soldier?’

‘No,’ the Azathanai replied. ‘He is Lord Anomander Rake, First Son of Darkness.’

Oh.

The lord then stepped forward, his attention fixed, not on Narad, but on Glyph. ‘We need not linger, if welcome is not offered. Denier, my brother haunts this forest. I would find him.’

Narad staggered back, his knees suddenly weak. A moment later he sank down on to his knees as the words of the evening just past returned to him.

‘Coming from where?’

‘From a holy shrine. From an altar black with old blood.’

He felt a hand upon his shoulder, a grip both soft and yet solid. With his own hands he had been clawing at his face, but now all strength left him, and they fell away, leaving him nowhere to hide. Shivering, eyes bleakly fixed on the ground before him, he listened to the storm in his skull, but it was a roar without words.

‘We know him,’ Glyph replied. ‘Look north.’

But the Azathanai spoke then. ‘Anomander, we’re not done yet here.’

‘We are,’ the Son of Darkness replied. ‘We walk north, Caladan. Unless this Denier lies.’

‘Oh, I doubt that,’ Caladan replied. ‘Still, we are not done yet. Bent Bow, your Watch suffers some unknown anguish. Does he refuse us welcome? If he does, then we must quit this forest—’

‘No!’ snapped Lord Anomander. ‘That we shall not do, Caladan. Look at this… this Yedan. He is not one of the forest dwellers. He bears a Legion sword, for Abyss’s sake. More likely we have stumbled into one of Urusander’s famous bandits—his very reason for invading the forest. I can now imagine them as godless as Urusander’s own, and a pact forged between the two.’

Narad closed his eyes.

‘A fine theory,’ Caladan said, ‘but, alas, utter nonsense. My lord, understand me—we walk lightly here, or not at all. We will await the word of the Watch, no matter how long it takes.’

‘Your advice confounds,’ Anomander said in a growl. ‘It is of a kind with all that now crowds me.’

‘Not the advice that confounds, lord, but the will that resists it.’

The hand on Narad’s shoulder was not a man’s hand. For this reason alone, he dared not open his eyes. Welcome to these two? How can I, without uttering the confession that now struggles to win free? Brother of the husband to be, I was the last to rape your brother’s would-be wife. I alone saw the light leave her eyes. Will you give me leave, good sir, to seek redress?

When Glyph spoke, his voice came from a few strides away, ‘His torment is not for you, Azathanai. Nor for you, Lord Anomander. Dreams make the path to waking, for the time of the Watch. We know nothing of that world. Only that its shaping is given form by anguished hands. And one of you, Azathanai or lord, now rattles that thing in his soul.’

‘Then name our crimes,’ Anomander said. ‘For myself, I will face them, and deny nothing that I have done.’

Narad lifted his head, but refused to open his eyes. Ah, this. ‘Azathanai,’ he said. ‘You are welcome here.’

Hunters now stirred, rising on all sides, taking hold of weapons. Anomander said, ‘So I am denied, then.’

Narad shook his head. ‘First Son of Darkness. The time is not yet for… for our welcome. But I will promise this. When we are needed, call upon us.’

At last, Narad heard the voices of his fellow hunters, their murmurs, their curses. Even Glyph seemed to hiss in sudden shock, or frustration.